The L.A.W. of the Empire of Morocco

The Glossary serves as a comprehensive guide, providing links to every item within this book. It is designed to assist students in completing assignments more efficiently and in a more organized manner, especially when multitasking.

Mission Statement

The purpose of this Dictionary is to connect the historical timeline of the Moroccan Empire to the present day, in conjunction with the AMPAC Study Sessions. Inside, you will find a wealth of information, including:

-

Moroccan History: A detailed account of the Moroccan Empire's past.

-

Treaties: Important treaties that have shaped the Empire.

-

Key Definitions: Essential terms defined for better understanding.

-

Maps: Detailed maps of all Moroccan territories.

-

Foreign Moroccan Countries or States: Information on foreign states within the Moroccan Empire.

-

Internal Moroccan States' Declarations of Independence: Key declarations from internal states.

-

Constitutions: Constitutions of all jurisdictions within the Empire of Morocco.

-

Laws: Internal and external laws governing Moroccan states and foreign jurisdictions within the Empire.

-

AMPAC Study Sessions: Documents and definitions discussed in AMPAC Study Sessions.

Continuous Updates

The L.A.W. of the Empire of Morocco will be continuously updated to ensure that the information remains current and accurate.

Special | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | ALL

I |

|---|

IMMUNITY OF STATE OFFICIALS FROM FOREIGN CRIMINAL JURISDICTION

Published under the auspices of the Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law under the direction of Professor Anne Peters (2021–) and Professor Rüdiger Wolfrum (2004–2020). A. Introduction1 The inviolability of diplomatic agents is one of the oldest rules of international law. Already thousands of years ago, in the practice of, for example, the Greek and the Romans, a diplomatic agent—then called a messenger or herald—was not to be maltreated or subjected to any form of arrest or detention. The immunity from the jurisdiction of the courts of the foreign State in which the agent performs his or her functions is of a more recent date, and can be traced back to the 16th century (Immunities). As far as criminal jurisdiction is concerned, the immunity rule quickly acquired an absolute status (Criminal Jurisdiction of States under International Law). Although it was at times argued that immunity did not extend to crimes against the receiving State—such as treason—early State practice did not reflect this position. When for example in 1584 the Spanish Ambassador to England was found to have partaken in a conspiracy against Queen Elizabeth, he was not arrested but sent back to his sovereign. The contours of the rule of immunity from civil jurisdiction were more controversial. Initially, there was considerable support for the position, put forward for example by Gentili, that ambassadors were not immune in respect of legal disputes concerning contracts entered into during the mission. It was not until the 18th century that diplomatic immunity from civil jurisdiction for acts not committed on behalf of the sending State became accepted as a rule of international law. 2 At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century several attempts at codification of the international law of diplomatic immunity were undertaken. The Institut de Droit international issued its Règlement sur les immunités diplomatiques in 1895 and a resolution on ‘Les immunités diplomatiques’ in 1929, in 1928 the Sixth International Conference of American States adopted the Convention Regarding Diplomatic Officers 155 LNTS 259, No 3581, and in 1932 the Harvard Research School published a Draft Convention on Diplomatic Privileges and Immunities ((1932) 26 AJIL Supp 15). Diplomatic law was among the first 14 topics that the newly established International Law Commission (ILC) selected for codification in 1949. The work of the ILC eventually resulted in the adoption of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (1961) (‘VCDR’; ‘Convention’). 3 Today this Convention has been ratified by over 190 States, and while in 1961 some of its provisions were not as much a codification of existing international law but rather a development of the law in view of the lack of consistent State practice (Codification and Progressive Development of International Law), the Convention has had a remarkable converging effect on State practice and has consequently shaped customary international law in the field. For the discussion of the rules of diplomatic immunity this contribution will therefore proceed from the relevant provisions of the Convention. In addition to the rules on the inviolability and immunity of personnel of a diplomatic mission, the rules on the inviolability of the diplomatic mission itself, and the rules protecting the archives and communications of the mission will be examined (see also Members of the Staff of Diplomatic Missions). It is no longer accepted to explain these diplomatic immunity rules in terms of Extraterritoriality. In modern international law the rules have a common rationale: ensuring the effective performance of diplomatic functions. The receiving State should not interfere with the work of the diplomatic agent—non impediatur legatio. 4 It should be noted at the outset that States may agree to accord more extensive privileges and immunities than required under the Convention on a reciprocal basis (Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (United Nations [UN]) 500 UNTS 95, UNTS Reg No I-7310, TIAS No 7502, 23 UST 3227, Art.47, (2), (b)). Moreover, Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (United Nations [UN]) 500 UNTS 95, UNTS Reg No I-7310, TIAS No 7502, 23 UST 3227, Art.47, (2), (a) provides that a receiving State may also apply ‘any of the provisions of the present Convention restrictively because of a restrictive application of that provision to its mission in the sending State’. The ILC commentary makes clear however that any restrictive application should stay within the bounds of the Convention. ‘It is assumed’, the commentary reads, ‘that the restrictive application in the sending State … is in keeping with the strict terms of the rule in question, and within the limits allowed by the rule’ (Draft Articles on Diplomatic Intercourse and Immunities with commentaries, adopted by the International Law Commission at its tenth session, in 1958 [[1958] II UNYBILC 89, UN Doc A/CN.4/SER.A/1958/Add.1, 89, UN Doc A/3859 (A/13/9), Ch.III, para.53], Section V Non-discrimination, Art.44 Commentary). In other words, the provision does not extend to the use of countermeasures in reaction to violations of the Convention (see also para. 34 below). 5 This contribution is limited to the rules applicable to permanent diplomatic missions. The position of ad hoc diplomatic missions will be treated in a different entry (Immunities, Special Missions). (Oxford Public International Law: Immunity, Diplomatic) Chapter V - United Nations - Office of Legal Affairs Immunities of State Officials, International Crimes, and Foreign Domestic Courts Immunity Privileges of Official Individuals | LawTeacher.net Revisiting Diplomatic Immunity in the 21st Century — Michigan Undergraduate Law Review Detailed Explanation1. Immunity of Consuls and Diplomats

2. Judicial Immunity

3. Executive Chief of Staff

4. Family Members

⚖️ Key Takeaways

So, the immunities are role-specific and do not automatically extend to executive staff or their families. Would you like me to break down examples of real-world cases where these immunities were tested (e.g., diplomats’ family members in criminal cases vs. executive staff lawsuits)? That could make the distinctions even clearer. 🏛️ Domestic Officials (like Chief of Staff)

👨👩👧 Family Members

✅ Conclusion: A State can attempt to issue diplomatic protection or even appoint the Executive Chief of Staff as a diplomat, but true diplomatic immunity only exists if the host country accepts the accreditation. Otherwise, the Chief of Staff and their family remain subject to local jurisdiction. Videos: Good Question: What Is Diplomatic Immunity? What is Diplomatic Immunity? What is Diplomatic Immunity? How Does Diplomatic Immunity Work? Why Diplomats Can't be Arrested Does Diplomatic Immunity Really Make It So You Can Get Away with Murder? No immunity for Israeli diplomat's son in cop crash case, officials say UN judge claims diplomatic immunity during arrest on modern slavery chargeshttps://www.youtube.com/shorts/RyOpwEkURxk IMF chief claimed diplomatic immunity when arrested The Worst Crimes Committed By Diplomats | NowThis World | |

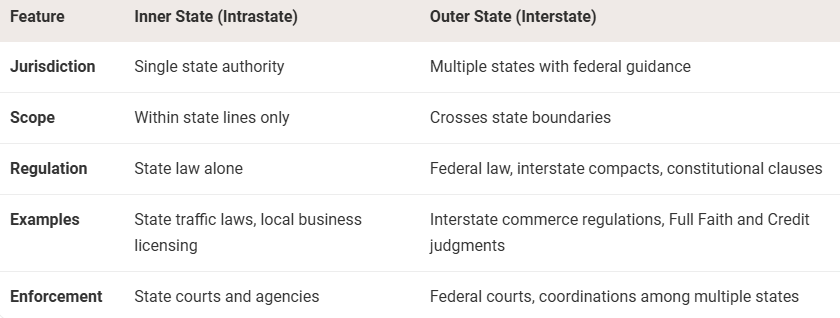

Inner & Outer Statesn legal terms, “inner” states (intrastate) refer to the authority and activities confined within a single state’s borders, while “outer” states (interstate) concern interactions or regulations that cross state lines or involve multiple states.

Inner States (Intrastate)

State governments exercise full sovereignty over these matters, subject to the U.S. Constitution

. Citizens and businesses are bound by the laws and regulations of the state in which they operate or reside

.

Outer States (Interstate)

Distinction and Legal Implications

Understanding whether a matter is intrastate or interstate impacts which laws apply, which courts have authority, and which agencies can enforce regulations

. Misclassifying the state scope can lead to conflicts between federal and state law, or between different state laws

In summary, inner states pertain to purely local jurisdiction and sovereignty, while outer states involve cross-border interactions requiring compliance between multiple states and often federal oversight, forming a foundational distinction in U.S. law and governance.

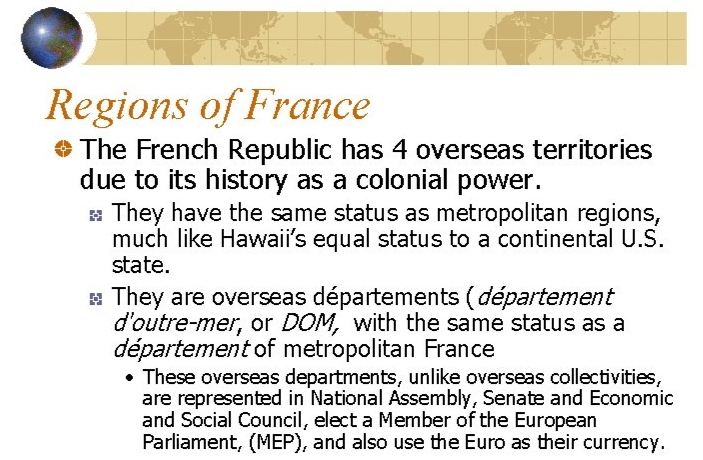

VIDEOS: Did You Know That France... 🇫🇷 #shorts #geography #maps #france France Still Has An Empire French Overseas Regions and Territories Explained | |

International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 1988 | |

Internet Web Browsers | |

Professor Pierre d'Argent

Professor Pierre d'Argent